Vijesh V. Krishna

Department of Agricultural Economics

University of Agricultural Sciences, Bangalore, India

N.G. Byju

Department of Agricultural Entomology

University of Agricultural Sciences, Bangalore, India

S. Tamizheniyan

Department of Agricultural Economics

University of Idaho, Moscow, Idaho

Regardless of political ideology, environmental issues are becoming paramount in all economic systems from the very poor to the very rich. India, one of the world’s largest agricultural economies, poses no exception. Demand for chemical pest control and resulting negative externalities have expanded greatly during the last four decades (Chand and Birthal 1997).

Three decades back, intensive and extensive cultivation of high yielding varieties of crops were introduced in India to increase food grain production. The new crop varieties and cropping sequences, especially monocropping, along with injudicious and indiscriminate use of pesticides created many problems. Several hitherto unimportant pest species began to cause economic losses. Others, especially polyphagous insects, have precipitated national problems (Srinivasa 1993). One glaring example is the old world bollworm, Helicoverpa armigera (Noctuidae: Lepidoptera), which caused a 66 per cent reduction in the yield of seed cotton in Andhra Pradesh State during the 1987-88 crop season. Previously, this pest only seriously affected rabi crops such as chickpea and was commonly known as the gram pod borer. Similar outbreaks have been reported for other insects: Whitefly in 1984-85 and 1985-86 in South Indian states, and tobacco caterpillar in 1977-78 and 1979-80 in the states of Tamil Nadu and Gujarat (Arunakumara 1995) and more recently, coconut mite, Aceria guererronis (Eriophyidae: Acarinae).

The agrochemical industry in India now produces 47,020 metric tons of pesticide (Directorate of Plant Protection and Quarantine 2002). Growth in pesticide consumption by Indian Agriculture is shown in Figure 1. Although pesticide consumption in India is low (around 500 g per ha) compared to other countries like Japan (12 kg per ha) and Germany (3 kg per ha), problems in India resulting from unregulated use are quite alarming. The predominant classes of pesticides used in India (during 2000-01) were insecticides, accounting for 61 per cent of total consumption, followed by fungicides (19 %) and herbicides (17 %) (Fig 2). In India, most pesticide use is on cotton (45%), followed by rice (22%) (Fig. 3).

In recent years, low external inputs and traditional techniques, including non-chemical alternatives, have been increasingly urged for India. These are viewed as technology options that could help create sustainable systems and decrease or avoid the needs for expensive and undesirable chemical inputs. Alternative agriculture has argued for an economically viable production to be viewed in the context of a healthier, environmentally friendly and sustainable chemical agriculture and the need for investment in low external input and non-chemical alternatives that include farmer empowerment. Numerous models exist and have been advocated and based on their respective inputs / nutrient management principles. They may be broadly classified into: (a) Integrated Pest Management (IPM), (b) Low External Input Sustainable Agriculture (LEISA), and (c) Organic Agriculture. Many sustainable agriculture initiatives and approaches based on these principles have now proved successful, with use of pesticides varying from more to only a limited amount. Of these, IPM is the one commonly advocated and widely adopted.

Status of IPM in India

India has an agrarian economy, where the 1012.4 million population is dependent on agricultural commodities from 124.07 million hectares cropped area cultivated by 110.7 million producers (Prasad 2001). For rapid dissemination of IPM information, IPM related activities are being implemented through 26 Central Integrated Pest Management Centers (CIPMCs) located in 23 States and Union Territories.

Major activities under the IPM approach include undertaking sample roving surveys for monitoring pest/disease situations on major crops, production and release of bio-control agents and conducting Farmers’ Field Schools (FFSs). Pest/disease situations are monitored regularly in the states covering 644,000 hectares (ha) of the targeted area of 469,000 ha. Pest situation reports received from field stations and states were compiled and comprehensive weekly and monthly reports circulated to the concerned officers and scientists of State Departments of Agriculture/State Agricultural Universities and ICAR Institutes to help them take appropriate remedial measures.

A total of 16,260 thousand bio-control agents have been mass produced in the laboratories and released (up to December, 2002) against insect pests in rice, cotton, sugarcane, pulses, vegetables and oilseeds (against the targeted release of 11,570 thousands during the year 2002-03. (40.54 % increase than expected) An area of 523 thousands ha has been covered against the targeted area of 367 thousands ha. in different states against various insect pests through augmentation and conservation (a 42.51 % increase over expected) (http://agricoop.nic.in/plantprotec02.htm).

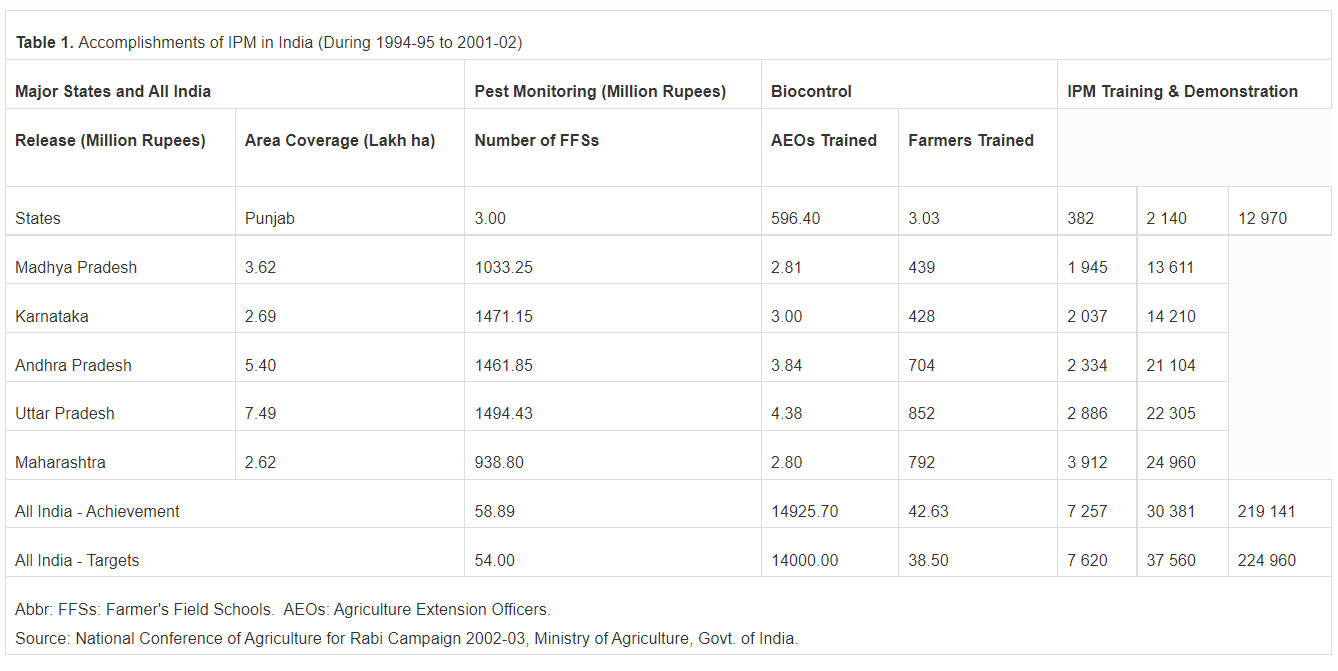

During the eight-year period from 1994-95 to 2001-02, the government of India spent nearly Rs. 14,926 million for biocontrol of pests on different crops, covering a land area of 4.3 million hectares. In addition to this, Rs. 59 million was spent for pest monitoring. The largest states of India, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Uttar Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh, and Karnataka, rank highest in accomplishing IPM. A smaller state, Punjab has also done well in IPM (Table 1). The disparity between different components of IPM accomplishment should be noted.

It can be also seen that the states that are progressing with IPM, are also ahead in using synthetic agrochemicals. Figure 4 indicates such a positive and significant relationship between consumption of pesticides and investment in IPM. This may indicate an increase in gross cropped area accounts for the increased expenditure on IPM rather than the policy changes of selected districts.

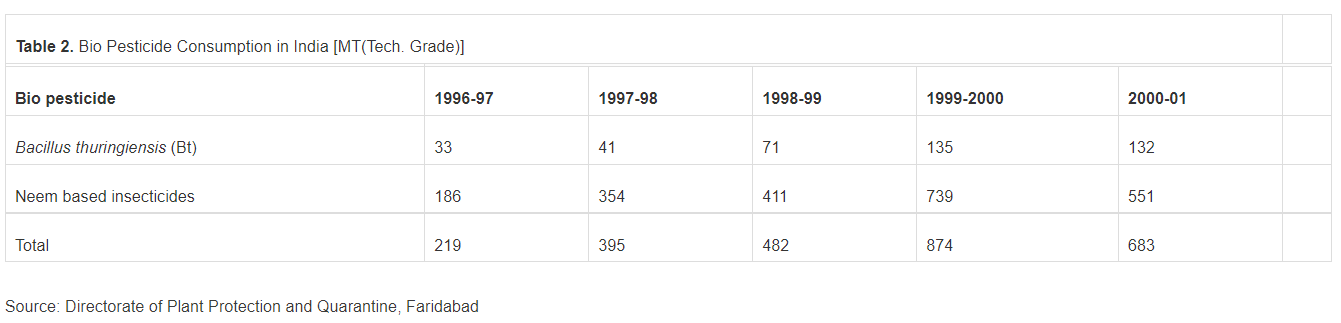

Table 2 shows the major bio pesticides consumed in India - Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) and neem-based insecticides. India needs an improved and newer group of bio pesticides. The exponential rate of increase in bio pesticide consumption (together with reduced synthetic pesticide consumption) is a positive sign that India’s agricultural community is becoming more concerned about the negative consequences of agrochemical usage.

Economics of IPM

To date, successful IPM programs have produced many benefits. These include (i) lower production costs (at farm level), (ii) enormous savings for governments from reduced pesticide imports and subsidies for pesticide use, (iii) reduced environmental pollution, particularly improved soil and water quality, (iv) reduced farmer and consumer risks from pesticide poisoning and related hazards, and (v) ecological sustainability by conserving natural enemy species, biodiversity, and genetic diversity.

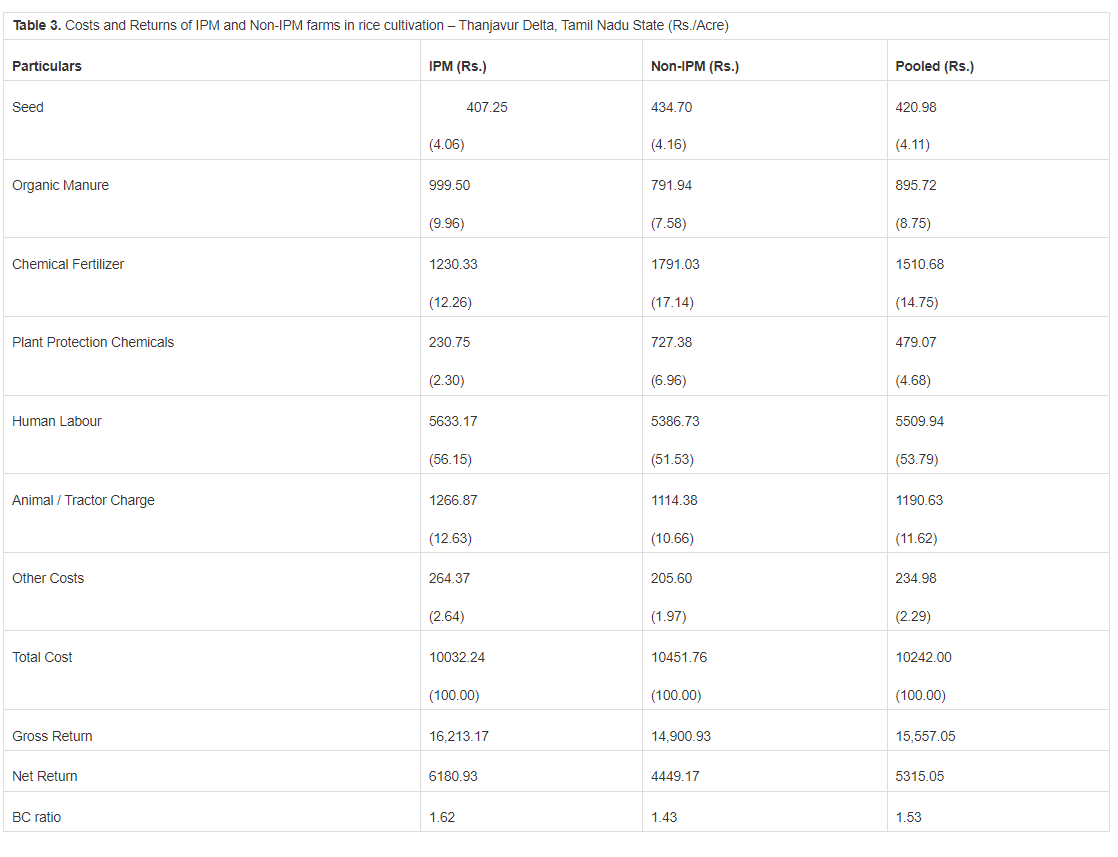

As mentioned earlier, the acceptability of a farming practice is primarily determined by short-term profitability. IPM attempts to integrate available pest control methods to achieve a farmer’s most effective, economical, and sustainable combination for a particular local situation. Studies have been carried out to examine the resource use pattern and profitability of IPM vis-à-vis non-IPM farming practices. The results of a recent study are presented in Table 3.

A study of the costs and returns of IPM and non-IPM farms in rice cultivation in the Thanjavur Delta of Tamil Nadu by Tamizheniyan during 2001 showed that IPM farms were resource efficient and more productive and profitable than non-IPM farms.

Note: Figures in parentheses show percentages to total cost.

Source: Tamizheniyan, 2001.

The total cost per acre on IPM farms was Rs. 10,452 compared to Rs. 10,032 on non IPM farms. The gross return was Rs. 16,213 compared to Rs. 14,900. The Benefit Cost Ratio was 1.62 for IPM, compared to 1.43 for Non-IPM farms.

Similar results were obtained in another study conducted on the economics of the IPM approach in Basmati rice (Garg 1999). The main aim of that study was to develop an IPM system in Basmati rice that would make farmers aware of the ill effects of indiscriminate use of pesticides and the benefits of IPM. Yield data showed that all IPM farmers secured higher rice yields than those using conventional chemical control tactics. It was also evident that farmer’s practice of not applying pesticide or very little pesticide was better than the indiscriminate use of pesticide which might have suppressed the natural enemy population.

Farmers’ perception about hazardous effects of Pesticides

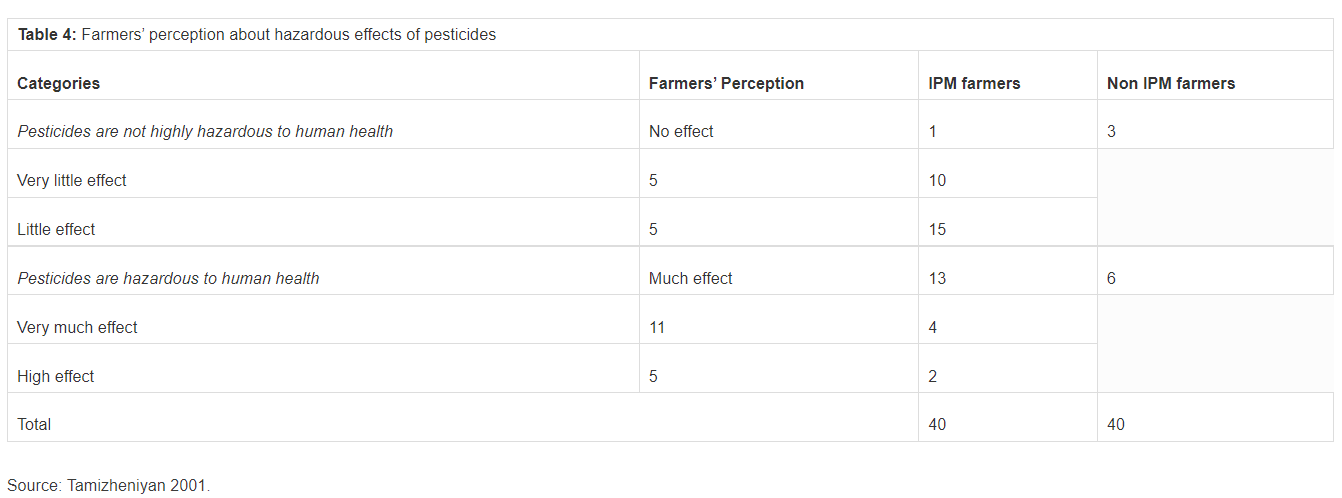

Although IPM has been accepted in principle as the most attractive option for protection of agricultural crops from the ravages of insect and non-insect pests, implementation at farm level in India had been rather limited (Puri 1998). Production uncertainty is commonly believed to be an impediment to adoption of less pesticide-intensive methods in agriculture such as IPM (Hurd 1994). To understand the Indian farmer’s perception about hazardous effects of pesticides, a survey was conducted among rice farmers following IPM and non-IPM practices in the Thanjavur delta, a major rice production belt of peninsular India (Tamizheniyan, 2001). The results are presented in Table 4.

It can be observed that the IPM farmers were more likely to see pesticides as causing hazardous effects to human health than were non-IPM farmers. One-sample c2 Test was employed (Appendix I) on these data and showed this observation to be statistically significant at a 5 per cent level of significance. This difference in attitude towards negative externality created by pesticide use might be acting as an impediment towards adoption of pesticide saving farming practices like IPM.Source: Tamizheniyan 2001.

Conclusion

The increasing cost of plant protection and accelerating pest incidents make agriculture a risky and less profitable enterprise. At the same time the toxic materials generated from chemical farming pollute the environment and harm consumers’ and farmers’ health. A more environmentally friendly and economical alternative for India would be adoption of Integrated Pest Management. Additionally, from the viewpoint of sustainability, attaining growth while maintaining the natural capital intact, IPM is superior compared to conventional farming (Chopra 1993). It should, therefore be appreciated and encouraged to a greater extent both by governments and NGOs'.

References

- Arunakumara, V.K. 1995. Externalities in the use of pesticides: An economic analysis in a Cole crop. MSc Thesis (Unpblished), UAS, Bangalore.

- Chand, Ramesh and Birthal, P.S. 1997. Pesticide use in Indian agriculture in relation to growth in area and production and technological change. Indian Journal of Agricultural Economics, 52(3): 488-498.

- Chopra, K. 1993.Sustainability of agriculture. Indian Journal of Agricultural Economics, 48(3): 527-537

- Garg, D.K.1999. Development of an IPM approach in Basmati rice. Annual Report, NCIPM, p: 13-19.

- Hurd, B.H. 1994. Yield response and production risk: An analysis of integrated pest management in cotton. Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics, 19 (2): 313-326.

- Karanth, N.G.K. 2002. Challenges of Limiting Pesticide Residues in Fresh Vegetables: The Indian Experience. In E. Hanak, E. Boutrif, P. Fabre, and M. Pineiro, (Scientific Editors), Food Safety Management in Developing Countries. Proceedings of the International Workshop, CIRAD-FAO, pp.11-13, December 2000, Montpellier, France.

- Prasad, S.S. 2001. Country Report – India. Report prepared for the meeting of the Programme Advisory Committee (PAC), Ayutthaya, Thailand, November 2001.

- Puri, S.N. 1998. Present status of Integrated Pest Management in India. Paper presented at Seminar on IPM, Asian Productivity Organization at Thailand Productivity Institute, Bangkok.

- Srinivasa, D.K..1993. Environment and human health. Environmental problems and prospects in India, Oxford and IBH Publications, New Delhi.

- Tamizheniyan, S. 2001. Integrated Pest Management in rice farming in Thiruvarur District of Tamil Nadu: A Resource Economic analysis. MSc Thesis (Unpublished), UAS, Bangalore.

| Appendix I: atistical Significance of Farmer’s Perception towards Hazardous effect of pesticides in rice farming | |

|

IPM Farmers |

Non-IPM Farmers |

|

Null hypothesis, H0: Perception of farmers is not different across all categories. Alternative Hypothesis, H1: Farmers think pesticides as hazardous for human health. |

Null hypothesis, H0: Perception of farmers is not different across all categories. Alternative Hypothesis, H1: Farmers think pesticides as not hazardous for human health. |

|

Level of Significance, a = 0.05 |

Level of Significance, a = 0.05 |

|

Degrees of Freedom, df = 5 |

Degrees of Freedom = 5 |

|

c2 calculated = 14.9 |

c2 calculated = 18.5 |

|

c2 table(a = 0.05, df = 5) = 11.07 |

c2 table(a = 0.05, df = 5) = 11.07 |

|

Decision: Reject H0 |

Decision: Reject H0 |

|

Conclusion: Farmers general perception is that pesticides are hazardous to human health |

Conclusion: Farmers general perception is that pesticides are not hazardous to human health |

Source: Computed from Table 4.